How the Dallas Cowboys Became an Entertainment Brand

Sports teams are technically supposed to play games. Win, lose, draw, whatever. But the truth is, they’re businesses first. Really good businesses, if you look at the numbers. Since 1960, owning a sports franchise has delivered an average annual return of 13.1 percent. The U.S. stock market over that same period? 10.54 percent. Which means if you had put a single dollar into a team back when Eisenhower was still president, you’d be sitting on $2,640 today. Not bad for something that also sells foam fingers.

But here’s where the story stops being about “sports franchises” and starts being about one franchise. Because one team isn’t just ahead of the pack. It’s lapping the field. According to Forbes, the Dallas Cowboys are the most valuable sports team in the world. More valuable than Real Madrid, more valuable than the Yankees, more valuable than the Patriots. And it’s not even close.

The explanation sounds simple, but the scale makes it ridiculous. The Cowboys just make more money than anyone else. In 2023, they pulled in $550 million in profit. Not revenue. Profit. That’s more than the Patriots and Rams combined. The Patriots came in second at $250 million, the Rams at $243 million, and the Cowboys just shrugged and doubled them both.

That’s how a football team in Texas became the most valuable sports franchise on the planet. Not by winning Super Bowls recently. Not by dynastic dominance on the field. Just by becoming the single most efficient money-printing machine in sports.

The Dallas Cowboys are even more impressive for one very obvious reason: they aren’t very good. And I say that as a fan. They haven’t touched a Super Bowl in decades. This year’s performance has been… let’s call it questionable. For years they were widely regarded as the most hated team in the NFL, a title only wrestled away by Kansas City in 2024.

So how is it that a team that can’t win big games is somehow the most profitable franchise in the world? And not just profitable. Popular. The Cowboys are the most searched NFL team on Google worldwide. They’ve built the most diverse revenue streams in football, and they’re the only team that doesn’t need to lean on NFL media revenue-sharing to make their money. They built their own empire and don’t have to split it.

Which brings us to the question worth obsessing over: how does a non-winning team become the most loved, the most hated, and the most profitable brand in sports?

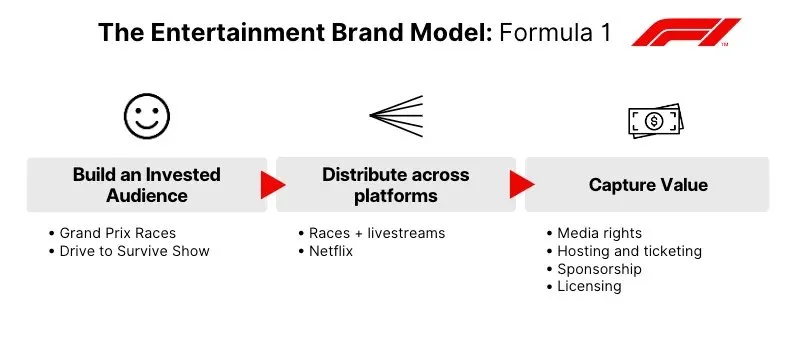

That’s where this Diary of a Brand introduces a new way to think about it. A framework for what I call entertainment-driven brands. Because once you start looking through this lens, the Cowboys sit right next to Formula 1 and Hailey Bieber’s Rhode Skincare. Three very different arenas. One identical playbook.

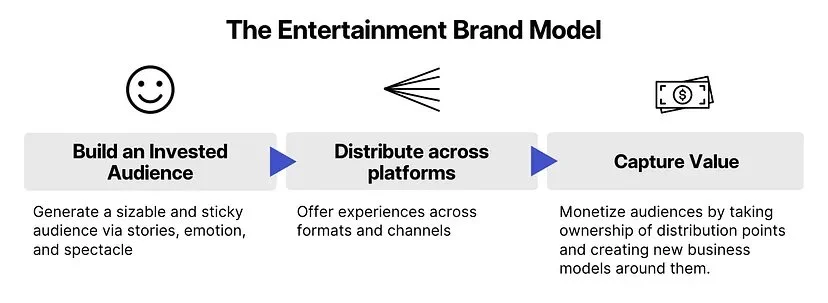

It runs in three phases:

Build an invested audience. Entertainment-driven brands get people hooked on the storyline. The Cowboys don’t need a trophy if everyone’s already desperate to see what they’ll do next.

Distribute across platforms. Disney is the masterclass here, spinning a single character into theme parks, movies, merchandise, and video games. The Cowboys use their stadium, their merchandising machine, and even just the idea of “America’s Team” as endless distribution points.

Capture value. Once you own the distribution, you can build business models around it. That’s why the Cowboys are the only team in the NFL that doesn’t depend on league revenue-sharing. They took ownership of their own distribution and turned fandom into a self-sustaining business.

That’s how a team that hasn’t been relevant on the field in decades manages to dominate off it. They aren’t just a football team. They’re an entertainment brand.

How the Cowboys Became the Most Valuable Sports Franchise in the World

Step one was never just about football. It was about building an invested audience. And for the Cowboys, that started with a man named Texas. Not the state. A guy literally named Texas. Texas “Tex” Schramm, former CBS executive turned Cowboys General Manager, engineered the early Cowboys into a media machine.

Schramm pitched the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders to boost attendance. It worked. So well, in fact, that every other team copied it and the squad became a pop-culture franchise on its own. He built the Cowboys’ radio network into the largest in sports by 1979. On television, he pushed the Cowboys into slots with the least competition: the late Sunday game, Thanksgiving Day, and, somehow, the NFC East, even though Dallas is about a thousand miles from Philadelphia. Why? Because the Eastern division gave the Cowboys constant games against New York, Philly, and Washington. The biggest media markets. More eyes, more stories, more national relevance.

“When else are people going to watch?” Schramm told the Tribune. “On Thanksgiving, you don’t have presents to open. You have dinner and football.” He was right.

He didn’t coin “America’s Team,” but the second NFL Films used it in a Cowboys highlight reel, Schramm printed 100,000 calendars with the tagline and flooded the market. Fans bought into the lore. Non-fans hated it. Either way, everyone had an opinion. And that was the point.

Schramm’s fingerprints went beyond Dallas. He lobbied for multi-color yard markers, goalposts painted bright yellow, arrows pointing to the end zone. He pushed instant replay, referee microphones, and play clocks. He helped invent the divisional structure and wild-card playoff slots. These weren’t gimmicks. They were ways to make the game more watchable, more dramatic, and more consistent as television entertainment. Don Shula said Schramm had “as much, or more, to do with the success of professional football as anyone.” That includes Pete Rozelle. That includes Vince Lombardi.

But an audience only sticks if the team actually wins. That’s where Tom Landry and Gil Brandt came in.

Brandt was the godfather of modern scouting. He looked everywhere nobody else was looking. Small schools. Foreign athletes. Track stars. Basketball players. He was the first to run player evaluations through computers. The first to layer in psychological testing. These ideas became the foundation of the NFL Combine. Under Brandt, the Cowboys drafted eight future Hall of Famers, starting with Bob Lilly in 1961.

Landry, meanwhile, turned schematics into myth. He invented the 4–3 defense with the Giants. In Dallas, he refined it into the “Flex Defense.” Suddenly, no matter where a runner went, a Cowboy was waiting. The unit earned the nickname “Doomsday.” Opponents called Landry a genius. By the end of their first decade, the Cowboys were not only relevant, they were Super Bowl champions.

That was step one. Audience built. Audience invested.

Step two was distribution. Cowboys owner Clint Murchison opened Texas Stadium in 1971. It wasn’t just a building. It was a prototype. The first stadium with luxury suites, sky boxes, personal seat licenses, preferred parking, and an exclusive club. Football wasn’t just a game. It was an experience.

Step three was monetization. Texas Stadium created a new kind of money. Suite revenue didn’t count toward the NFL’s revenue-sharing pool. Which meant while everyone else split television money, the Cowboys printed their own cash. With 176 skyboxes, the revenue was massive. Today, luxury seating across the league is standard. For the Cowboys, it generates around $130 million annually.

By the time the dust settled, Dallas had created the blueprint: build an invested audience, spread them across platforms, and then capture value. Schramm, Landry, Brandt, and Murchison didn’t just build a football team. They built an entertainment brand decades before anyone called it that.

The Jerry Jones Era: Monetizing the Brand

The Cowboys didn’t actually become the most valuable sports team on earth until Jerry Jones showed up in 1989 and bought the whole operation. And for better or worse, he’s been running it ever since. Jones is polarizing, especially among Cowboys fans. But this isn’t about his play-calling, his draft choices, or his sideline cameos. It’s about how he turned Dallas into a money-printing juggernaut.

Before Jones, the NFL kept sponsorships and merchandise on lockdown. Everything was centralized. The league signed the deals, split the checks, and every team got the same slice. Then came the mid-90s Cowboys. Fresh off two Super Bowl wins, Jones decided to break formation. Dallas signed its own deals with American Express, Pepsi, and Nike, and even turned assets like Texas Stadium and his coaches’ clothing into revenue streams the league couldn’t touch.

Jones knew the math. NFL sponsorship money was split 32 ways. Stadium sponsorship money? 100 percent Cowboys. He was the first owner to cut independent deals at Texas Stadium. Nike even agreed to pay Cowboys coaches to wear the swoosh on the sidelines. That sounds normal now, but in the mid-90s it was radical.

And Jones didn’t just sign the contracts. He staged a spectacle. On Monday Night Football, in front of a national audience at Giants Stadium, he strutted to the Cowboys’ sideline with Phil Knight, Nike’s chairman, and Monica Seles, Nike’s star endorser. He literally distributed a press release announcing, “Cowboys Owner Bucks N.F.L. Again.” It wasn’t business. It was theater.

The NFL sued. Jones countersued. His defense was simple: these weren’t team deals, they were stadium deals, and Texas Stadium belonged to him. Television and gate revenues? Sure, those could be shared. But the logos on his building and the apparel on his staff were his to sell. He even called for the outright death of NFL Properties, the league’s central licensing arm, dismissing it with a one-liner: “You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to do better than they did. You wake up in the middle of the night thinking of ideas.”

Eventually, the NFL blinked. Jones kept his deals, and the precedent was set. Suddenly, stadiums weren’t just places to play football. They were sponsorable platforms, business ventures in their own right. Other owners noticed. Merchandise followed. The floodgates opened.

What Jones really did was rewire the league’s economics. He proved a team could be more than its share of NFL money. It could be a standalone brand, carving out its own empire inside the structure of the league. And in that world, Dallas was perfectly positioned to lead.

The Cowboys and the Merchandise Loophole

In 2001, the NFL signed a league-wide merchandise deal with Reebok. Buried inside was a clause that let teams spin off their own merch operations if they wanted. Out of 32 franchises, exactly one raised its hand. Dallas. Of course it was Dallas.

But here’s the thing: the Cowboys didn’t just cash checks. They didn’t treat merchandise like another logo slapped on another hoodie. They ran it through the same entertainment-driven playbook they had been using since Tex Schramm. Invest in audience. Expand distribution. Then capture value.

Last year, that strategy looked like Post Malone. Dallas collaborated with the rapper on a line of Cowboys-themed clothing, which was already guaranteed to sell because it combined two fanbases: the team and the artist. But the Cowboys didn’t stop there. They added a new layer of distribution. They turned it into an experience.

The collab showed up not in a store, not in a stadium, but at a Raising Cane’s. A chicken chain turned into a Cowboys x Post Malone x Cane’s mashup, serving chicken fingers alongside exclusive merch and even vintage Cowboys collectibles. You walked in for lunch and left with a piece of the Cowboys brand.

That’s the model in action: take a clause nobody else uses, treat it like a stage, and then pull it into new spaces until it becomes more than merchandise. It becomes entertainment.

Jerry World and the Modern Media Machine

If the old Cowboys empire was built on Texas Stadium, the modern one is built on something bigger, louder, and almost comically outsized: AT&T Stadium. Everyone just calls it Jerry World.

In 2009, Jerry Jones doubled down on Clint Murchison’s legacy by opening the largest stadium in the NFL. A building so massive it features the world’s largest HD video display and an expandable capacity north of 100,000. Like Texas Stadium before it, the place is a revenue fountain. Ticket sales. Luxury seating. Plus a naming-rights deal with AT&T worth an estimated 17–19 million annually. Even the bars are sponsorable platforms. The Miller Litehouse isn’t just a place to grab a beer, it’s part of a $20 million annual Cowboys sponsorship from Miller Lite.

But Jerry World isn’t just about football. It’s a content machine. The building has hosted everything from Taylor Swift concerts to college football games to Netflix’s boxing circus with Mike Tyson and Jake Paul. Every time another event rolls through, the Cowboys get paid. It diversifies the revenue stream far beyond wins and losses.

This isn’t just Dallas. Stadium ownership has become the dividing line between “wealthy team” and “world’s most valuable team.” Look at Los Angeles. The Rams are valued at $8 billion. The Chargers? $6 billion. Both play in the same building, but the Rams own SoFi Stadium and the Chargers rent it. Which means the Rams pocket 85 percent of suite and partnership revenue, all the non-NFL event money, and the full $625 million from SoFi’s naming-rights deal. Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour alone supposedly drove $4 million per show for the Rams.

Owning platforms is good business.

And Jerry Jones knows that building a platform isn’t just about bricks and naming rights. It’s also about media. He personally hosts celebrities at games, walking them through the tunnels in plain view of cameras, manufacturing moments that get picked up by social feeds and entertainment news. The spectacle multiplies. The Cowboys don’t just sell tickets. They sell the idea of being seen at Jerry World.

Building a Media Army

The Cowboys don’t just play football and they don’t just sell tickets. They also run one of the largest in-house media operations in the NFL. This isn’t just a couple of videographers shooting highlight reels. It’s a full-scale content studio. Documentaries. Behind-the-scenes footage. A social media presence that feels more like a brand network than a football team.

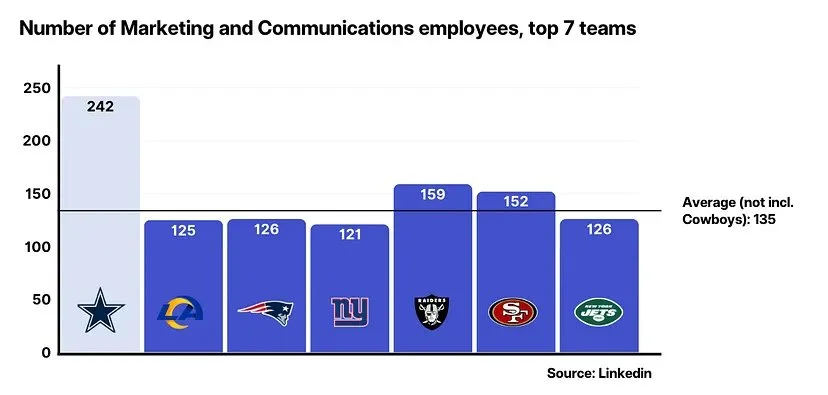

It’s hard to pin down exactly how much they spend on media since NFL teams are private companies, but there are ways to measure scale. A quick look at LinkedIn shows the Cowboys employ 242 people in Marketing and Communications. Compare that to the next six most valuable teams, who average 135. Dallas is choosing to staff more than 100 additional content producers, marketers, and designers.

The Cowboys treat media the same way they treat luxury suites or naming rights: as a platform. More storytellers mean more storylines. More storylines mean more reach. And more reach means the Cowboys keep multiplying their audience even when the product on the field isn’t delivering championships.

The Star: Headquarters as a Platform

Most teams treat headquarters like an office. The Cowboys treat theirs like Disneyland.

The Star in Frisco, Texas, is not just a practice facility. It’s a full production campus. Inside, the Cowboys’ media army has access to a broadcast studio, podcast studios, multiple editing suites, and corporate event spaces. There’s even space carved out so partner brands can shoot content or stage live events. That investment pays off. The Cowboys have the largest social media following of any NFL team across Instagram, Facebook, X, and TikTok. When they post, the audience is already waiting.

But in true entertainment-brand fashion, the Cowboys didn’t stop at making The Star a production hub. They turned the building itself into another monetizable platform. The Ford-sponsored Ford Center doubles as a practice field and a venue for local sports. The Tostitos Championship Plaza is billed as a “destination for connecting fans with the Dallas Cowboys.” The complex also includes a hotel, a members-only club, a Cowboys-branded fitness center (one of five locations), a second Miller Litehouse, and a full shopping and entertainment district with sponsored events layered into the experience.

It’s not just HQ. It’s real estate that functions as marketing, media, and business all at once.

As Robert Covington of Braemont Capital put it: “Jerry Jones was a trailblazer in really thinking about a sports team more like a business, like a Disney. There’s merchandise, there’s the media rights, there’s the fan experience … there’s the real estate around the stadium.”

And compared to other NFL teams, the diversification shows up in the numbers. Each team gets about $480 million annually in shared media revenue from the NFL. But Dallas stacks revenue streams on top of that: leading the league in luxury suite income (an estimated $130 million annually, per Forbes) and piling on platform-based revenues from The Star and AT&T Stadium. Private ownership means not every number is public, but one thing is clear. The Cowboys’ business isn’t just stronger. It’s broader, deeper, and more diversified than anyone else’s. And it’s not close.

The Entertainment Brand Model: Dallas Cowboys

The Cowboys aren’t just a football team. They’re the proof-of-concept for what I call the Entertainment Brand Model. The formula looks deceptively simple: build an audience, distribute across platforms, and then monetize those platforms with new business models. But in practice, Dallas has been refining it for decades.

Look at the two phases of ownership. Clint Murchison in the early years. Jerry Jones in the modern era. Different personalities, different approaches, but the same through-line: invest in the audience first. Schramm and Landry built the Cowboys into “America’s Team” long before the dollars started rolling in. Jones later proved that an invested audience could be monetized across sponsorships, stadiums, media, and merchandise.

That’s the core lesson of the Entertainment Brand Model. Audiences aren’t just viewers. They’re assets. And if you build them the right way, they can outlast wins, losses, and even decades without a Super Bowl.

Can Other Brands Apply the Entertainment Brand Model?

Yes. But only if they’re willing to flip the usual playbook upside down. Most businesses run product-first. Build the thing, then figure out how to market it.

Entertainment brands start with story. They build an audience before they ever sell a product. They craft spectacle people can’t look away from. And once the audience is hooked, then the monetization comes. Sponsorships. Products. Experiences.

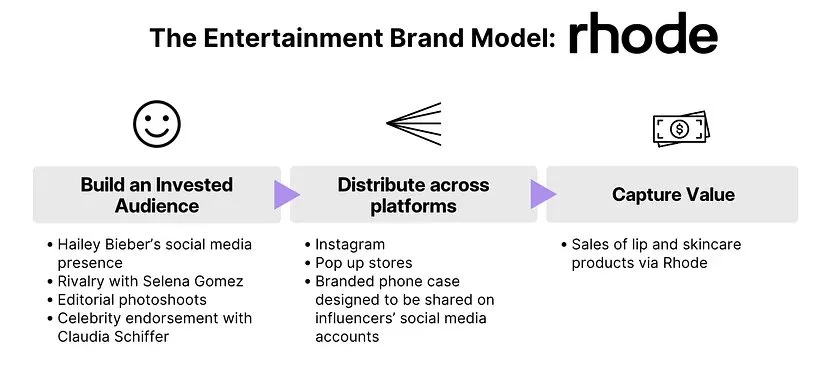

That’s exactly what the Cowboys have done twice. In the 1990s, it was cheerleaders, rivalries, and Super Bowls. Today, it’s AT&T Stadium and celebrity tunnels, minus the Super Bowls. But the same logic applies outside of football. Hailey Bieber built Rhode on top of her social media following and celebrity coverage. Kim Kardashian did the same with SKIMS. Neither brand starts with fabric. They start with story.

The Cowboys just happened to write theirs in pads and helmets.

Hailey Bieber didn’t launch Rhode in a vacuum. She already had a massive built-in audience on social media. Every post, every paparazzi shot, every magazine cover came with millions of eyes attached. The media’s obsession with putting her in contrast to Selena Gomez only poured fuel on the fire. The drama became part of the narrative, which meant more attention, which meant more audience.

And once the audience was there, Bieber ran the Entertainment Brand Model to perfection. She invested in editorial-level content, treating Rhode not just as skincare but as part of a bigger aesthetic universe. Then she monetized that attention with products. Rhode became less about moisturizer and more about being part of Hailey Bieber’s ongoing story.

That’s the key. The product didn’t create the brand. The story did.

Other sports brands have followed the same model. Formula 1 is now the fastest-growing sport by revenue, and the turning point wasn’t new cars or new rules. It was Drive to Survive.

The Netflix series reframed the sport as rivalries and personalities, turning lap times into drama. Suddenly, F1 wasn’t just racing. It was bingeable storytelling.

How to apply the Entertainment Brand Model

1. Build an Invested Audience Through Stories

People don’t want to pay attention to brands. Formula 1 proved this. Most fans didn’t care about a car chase at 200 mph. What did they care about? The people behind the wheel.

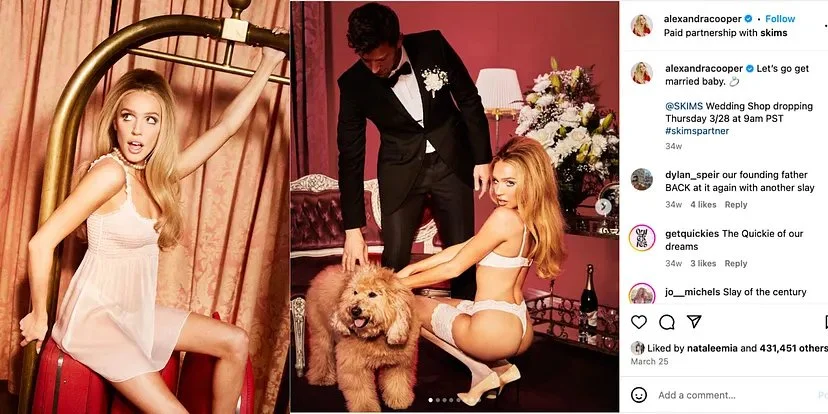

That’s why hiring celebrities and influencers works. Not because of the endorsement, but because of the story. A celebrity in your ad isn’t a story. A celebrity in the middle of a life event is.

Alex Cooper, host of Call Her Daddy, getting married? That’s a story. SKIMS partnered with her on a wedding line right before her highly publicized marriage, and the audience followed.

For your brand: What stories about people can you tell that are impossible to ignore?

Characters as Story Engines

Not every story needs a celebrity. Sometimes brands just invent their own characters.

Chipotle leaned into its farm-to-burrito positioning with its “Farmer” series. Dunkin went viral on Halloween with the bizarre but unforgettable “sexual spider donut.” Both worked because they gave audiences something to follow beyond the product.

If you want to build an audience, brief a freelancer to pitch you content series and characters. A burrito farmer or a spider donut might sound ridiculous. But ridiculous gets remembered.

2. Distribute Across Platforms

Entertainment brands don’t stay in one lane. They turn a single story into multiple channels. Disney is the blueprint: every piece of IP becomes a movie, a Broadway show, a video game, a toy, and a theme park ride. Same story, five different revenue streams.

Victoria’s Secret did it too. Underwear became a spectacle with the Angels fashion show. The product was fine. The distribution point made it cultural.

For your brand:

If you sell a product, how could it become an experience? (Haircare as a pop-up salon.)

If you sell an experience, how could it become products or something more immersive?

3. Monetize

Distribution is only half the game. The next step is turning those touchpoints into revenue. Events can charge admission. Products can expand into adjacent categories. Sponsors can pay for the exposure.

Chipotle launched its own hot sauce. A bookstore can host sponsored book clubs. SKIMS turned shapewear into athleisure and subscriptions.

The key: don’t be boring. Entertainment brands win because they entertain. They invest in content, find the touchpoints audiences already care about, and deliver there.

The Cowboys understand this better than anyone. They don’t just play football. They stage shows. They build new platforms. They invent business models around those platforms. That’s why they’re the most valuable sports franchise in the world. And here’s the kicker: they’re making double the profits of their closest competitors, while only being valued 37 percent higher. Which means, by the math, the Cowboys might actually be undervalued.