How Taylor Swift and Restaurants Turn Scarcity Into Profit

Taylor Swift priced the average Eras Tour ticket at $253.56.

But that number mattered for about as long as it takes Ticketmaster to crash, which is to say not long at all. Fourteen million people tried to buy tickets. Fourteen million. The resale market responded by detonating that $253 into an average of $3,801. That is not inflation. That is metamorphosis. And while you might think this sort of thing only happens with global pop stars, restaurants have quietly been doing the same trick. ResX and Cita now run marketplaces where you can buy and sell dinner reservations like scalpers flipping floor seats. Want Carbone, the restaurant where the pasta comes with a side of celebrity sightings? That will be $200 to $600. Lilia, Brooklyn’s cathedral of pasta? Same thing. And remember, that is before you have even touched a menu.

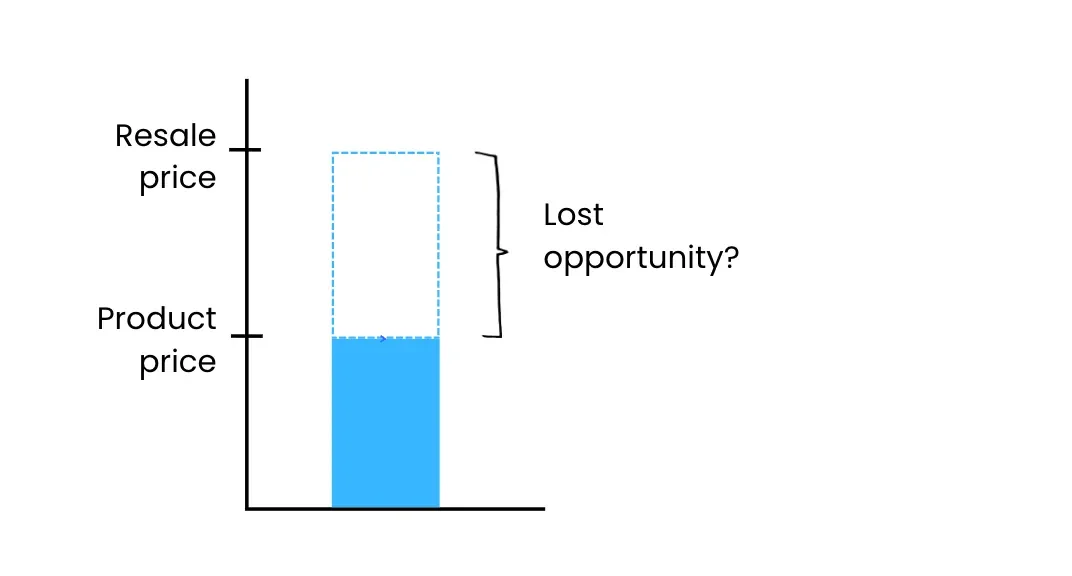

So here is the obvious question. If people are willing to pay $600 for a table, why not raise the menu prices and take the money directly?

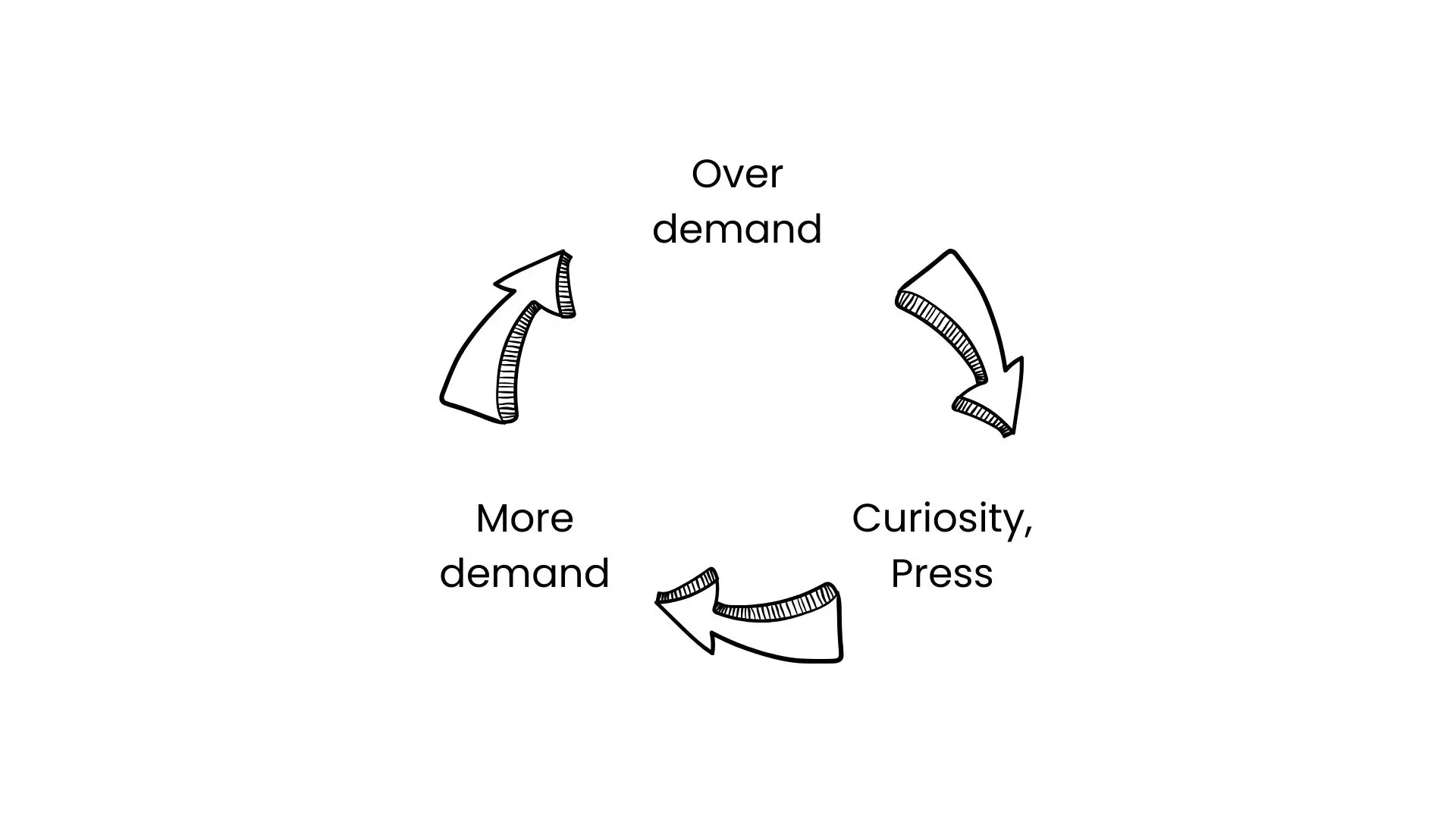

Because the line out the door is not just evidence of demand. It is the generator. You see twenty strangers queuing on a sidewalk and suddenly you are building the myth in your own head. Maybe you should eat there. Maybe everyone else knows something you don’t. And then you hear about Taylor Swift’s website collapsing under its own weight, and the concert transforms from a night out into folklore. Scarcity does not whisper. Scarcity has a megaphone.

And that megaphone builds a loop. Too little supply feeding too much demand.

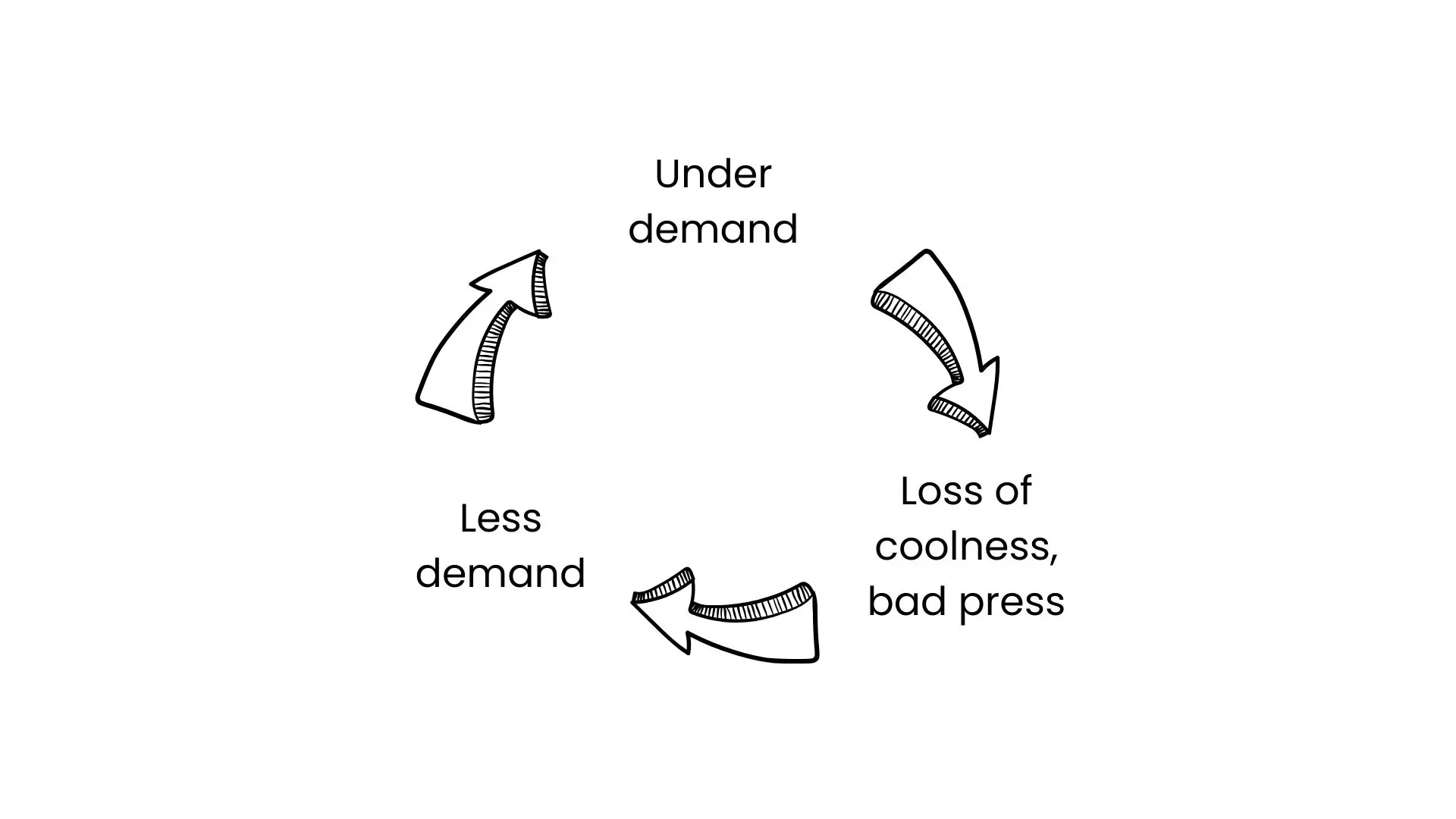

Yes, some places cash in with headline pricing. Serendipity3 sells a $214 grilled cheese. A Wagyu katsu sandwich once went for $180. But those are gimmicks. They are designed for Instagram captions, not anniversaries. The institutions know better. Taylor knows better too. The Eras Tour is not just about pyrotechnics. It is about dads in parking lots waiting for their daughters to come out hoarse from screaming along. If every ticket had been $1,000, that moment disappears. Worse, if the resale market cooled instead of overheated, the narrative would flip from “Taylor broke the economy” to “Taylor overplayed her hand.” And once that happens, the cycle does not just stop. It reverses.

Which is why chasing demand is such a dangerous game.

Scarcity is powerful, but it is brittle. Push too hard and the aura shatters. The smarter move is to create consolation prizes. Products that are easier, cheaper, infinite — but still orbit the scarce original. Taylor cracked this with the Eras Tour movie. It is not just a concert film. It is a pressure valve. It takes demand that stadiums could never possibly hold and releases it across theaters, streaming services, and rewatches that can number in the millions. The scarcity of the live show did not fade. It became the marketing for everything else.

Restaurants have been running the same experiment. Lilia spun off Misi, which spun off further still by selling pasta and ricotta so fans could recreate ricotta toast in their own kitchens. Rao’s, the Harlem restaurant where reservations are a local legend, sold its pasta sauce line to Campbell’s Soup for $2.7 billion. The restaurant is not famous because of the sauce. The sauce is famous because of the restaurant. Scarcity became scale.

So here is the secret. Raising prices to smother over-demand is the boring option. Using over-demand as the launchpad for whole new businesses? That is the genius move.