Peloton’s Turnaround Playbook: Marketing, Gyms, and the Future of Fitness

Peloton announced quarterly earnings last week. And the story, once again, was the same movie we have all seen before: revenue beats, losses beat too, and investors sigh as they close the tab on their brokerage apps.

The problem was not people trying Peloton. That part is easy. The problem was getting those people to stay. A free trial is fun. A subscription is a commitment. And Peloton is still struggling to bridge that gap.

So, how do you fix that? How do you take a company that was once a cultural shorthand, the exercise bike that became a pandemic phenomenon, the Christmas ad meme, the Zoom-era status symbol, and turn it into a sustainable business?

Step 1 — Analyzing Peloton’s business

Here is the twist: I actually like a lot of what Peloton has been doing lately.

Last year they hired Leslie Berland, the former CMO of Twitter, and the marketing shift was instant. Gone were the shots of Peloton bikes parked in Manhattan penthouses with 30-foot windows and suspiciously well-behaved golden retrievers lounging in the corner. In their place? People sweating in garages. People squeezing in twenty minutes between Zoom calls. A Peloton wedged awkwardly next to the laundry machine. For the first time, Peloton ads started looking less like a movie set and more like a life.

But is that less aspirational? Shouldn’t they be selling the dream?

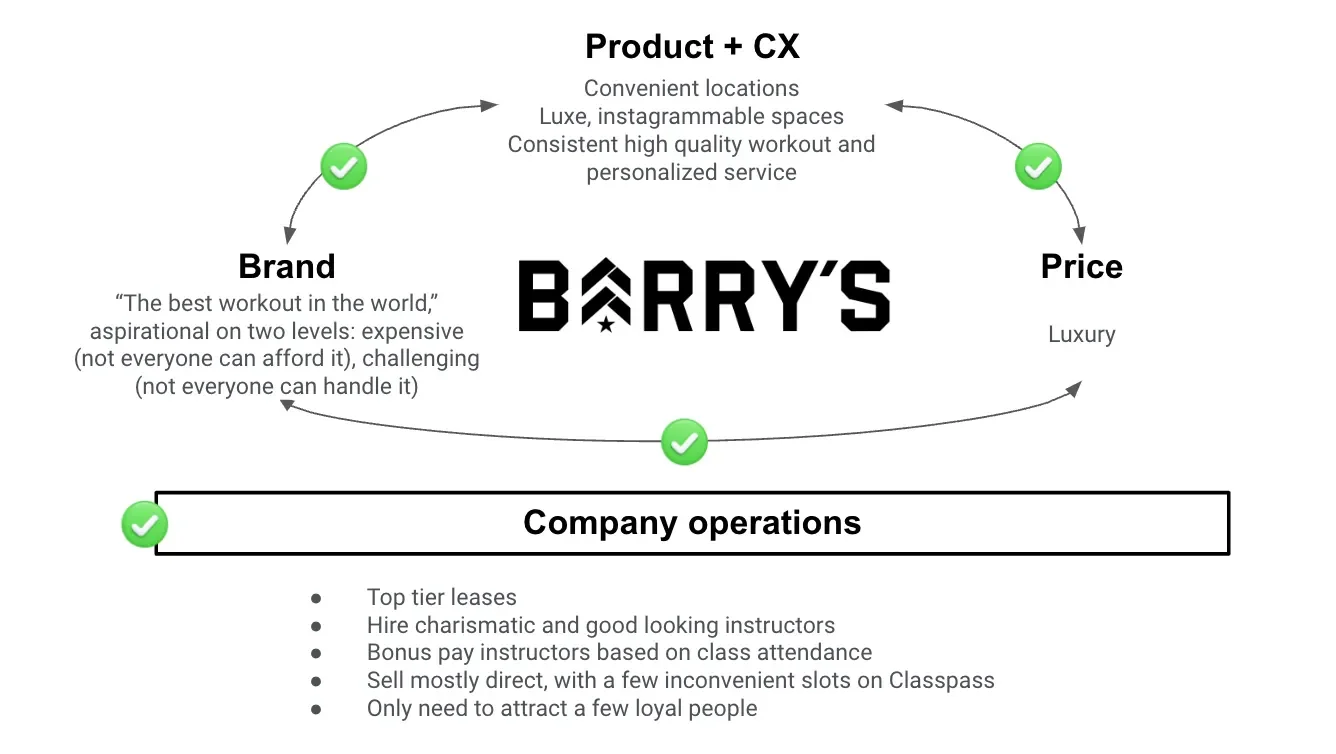

No. That is the point. Peloton leaned too hard into the dream already. Their business model is not Barry’s Bootcamp. It is Netflix. You pour money into creating expensive content, and then you make that money back by scaling it across as many people as possible. If you want to sell the masses, you cannot keep marketing to the Hamptons.

Barry’s Bootcamp, on the other hand, is built for luxury. The whole thing depends on scarcity. A studio can only fit so many people, so the only way to make the numbers work is to charge a fortune. Forty bucks for fifty minutes of treadmill sprints and floor work. Fifty if you are in the Hamptons. And because it is luxury, the experience has to scream luxury: mirrored walls, flattering red lighting, Dyson hair dryers, Oribe shampoo. Even the post-class selfie is part of the product. I have done it. Guilty.

The point is, Barry’s can live at that high price point because every piece of their flywheel, price, product, brand, operations, reinforces it. The wheel spins smooth.

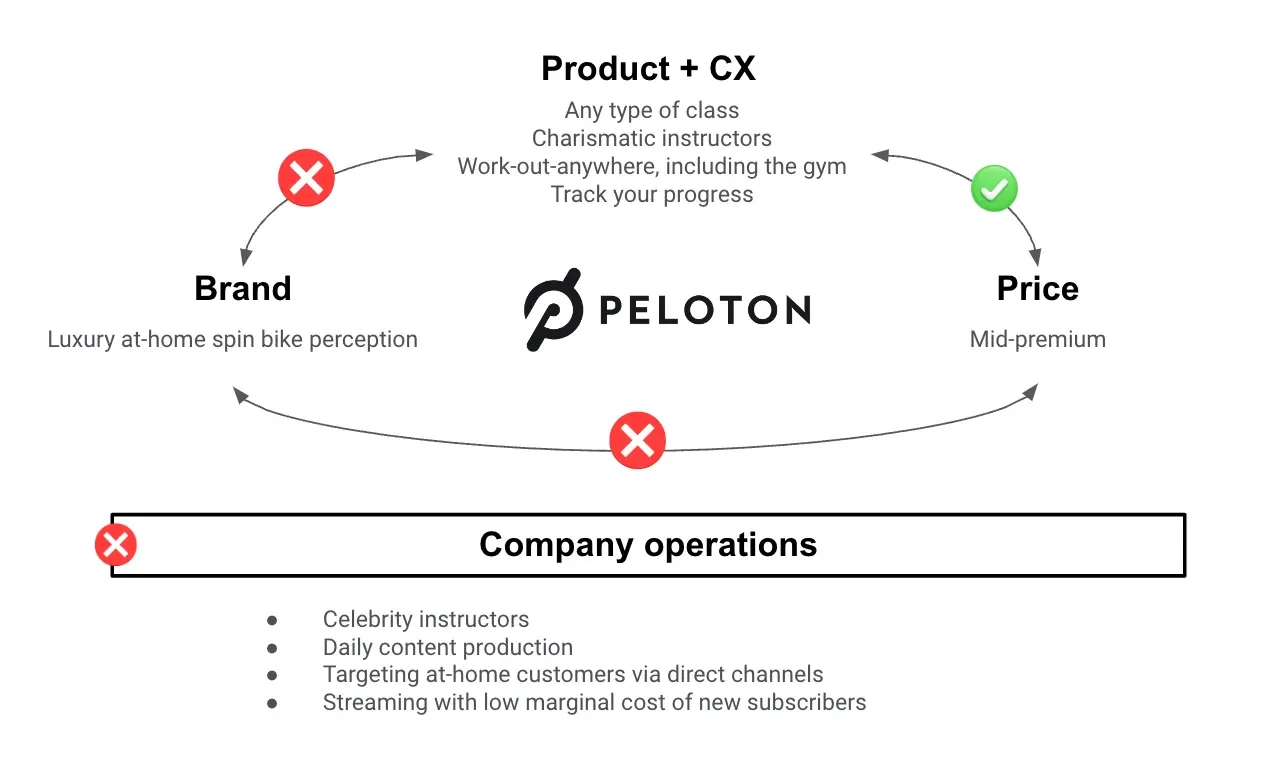

Peloton’s wheel? Wobbly.

Here is why.

First, Peloton is still perceived as luxury. That is the hangover from the old ads. But if you crunch the math, the value proposition looks different. The bike is $1,445. The all-access subscription is $44 a month. Keep the bike for two years and you are paying $105 a month for unlimited classes with some of the best instructors in the world. That is not luxury. That is the price of two and a half Barry’s classes. And if you are just a digital subscriber like me? It is $24.99 a month. At that point, it is cheaper than cable.

Second, the spin bike problem. Peloton offers strength training, barre, yoga, boxing, Pilates, meditation, rowing, running, stretching. The list keeps growing. But the mental shortcut people still use is: Peloton = bike. That perception closes doors before people even look at what the app actually does.

Third, the at-home stigma. This is the stickiest one. During COVID, Peloton was the perfect product at the perfect time. Lockdowns made everyone a captive audience, and Peloton won the at-home category by default. But once gyms reopened, the narrative flipped. Suddenly it was a binary choice: are you a gym person or a Peloton person? Pick one. That is the false binary cutting Peloton off from the exact people who are most willing to pay for fitness, gym goers. Instead, they have been forced to chase the hardest audience possible: people who do not already have a fitness habit. That is like opening a steakhouse and deciding your best growth strategy is convincing vegans.

The fix? Break the binary. Stop marketing Peloton as a replacement for the gym. Start selling it as a complement.

Nike cracked this code with Nike Training Club. Nobody thought the app meant gyms were over. It was just something you could use inside the gym. Peloton could position itself the same way.

And if you need proof of how powerful complements are, look at Apple in the early 2000s. The iPod did not kill CDs overnight. It lived alongside them. For years, people bought both. That overlap gave Apple time to build dominance. Peloton could pull off the same trick.

Back to Peloton

Right now, their flywheel is misaligned. The brand still whispers “luxury” even though the math says “premium.” The product is bigger than the spin bike, but the perception has not caught up. And the false gym versus Peloton dichotomy is cutting them off from their best audience.

Step 2 — Codifying Peloton’s marketing challenges

So where does that leave us? If you spin the Brand Flywheel, a few spokes start wobbling. Four, to be exact.

Challenge one: Shift price perception from luxury to premium.

Peloton has already started this. The garage-bike ads, the more realistic settings — all moves in the right direction. But the perception hasn’t caught up yet. And perception is everything. If the world thinks you are a Hermès scarf when you are really more like a J.Crew cashmere sweater, you are stuck in the wrong tax bracket.

Challenge two: Shift perception from spin-only to all-around fitness.

Peloton’s got a full buffet — yoga, boxing, barre, Pilates, meditation, strength — but people still see them as the salad bar with one item: the bike. They tried fixing this with a glossy ad. Great soundtrack, slick editing, lots of sweat. But it was basically the “let’s throw everything we have into a montage” approach. Which is the ad equivalent of someone asking, “So what do you do?” and you answering, “Well, I can juggle, and I’m good at trivia, and I once met Ryan Seacrest.” True, maybe, but not convincing.

Challenge three: Peloton needs a story.

Everyone knows the name. What they don’t know is why they should care now. Peloton has been frozen in cultural amber since the pandemic boom. People remember the pandemic bike craze. They remember the ad that launched a thousand parodies. They remember “that thing I almost bought in 2020.” But there hasn’t been a new chapter. Brands live on story. Right now Peloton’s story is an unfinished sentence.

Challenge four: Get into gyms.

This is the sneaky one. Distribution doesn’t sound like brand, but it absolutely is. When Moncler wanted to jump from “ski jackets” to “luxury fashion staple,” one of their first moves was to pull out of sporting goods stores and only sell in luxury boutiques. Where you show up tells people what you are. Peloton showing up only in homes? Niche. Peloton showing up in gyms? Mass market.

And that is the fork in the road.

Step 3 — Answering the challenges

So how do you fix all of that?

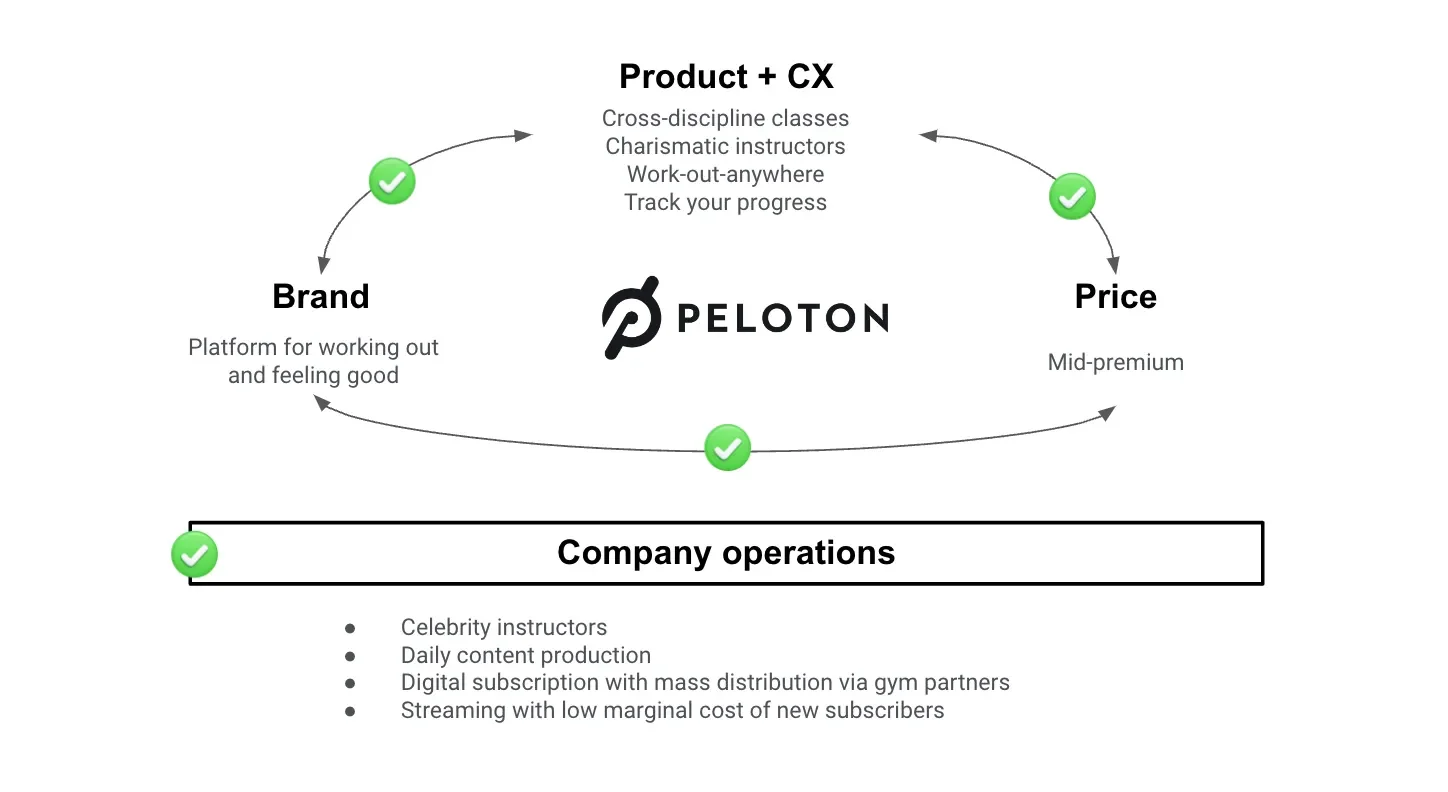

The first three problems — price, spin perception, and story — can all be attacked with a single creative campaign. The fourth, gyms, is a distribution play. Put them together, and the flywheel starts spinning.

Campaign idea 1: Mental health is physical health is mental health

Here is a confession. I did not start working out regularly until I stopped caring about the physical side. What clicked was the mental part. Exercise wasn’t about abs or calories. It was about not feeling like garbage. And that’s not just me. Research piles up every year about the mental health benefits of exercise. And mental health? That’s a cultural conversation people actually want to have.

Peloton could own this space. They already have an instructor, Kendall Toole, who talks openly about mental wellbeing on her social channels. Imagine if Peloton leaned into that vulnerability. Imagine if the brand said, “This isn’t about a six pack. This is about not yelling at your dog after a bad day.” That is a platform.

And platforms scale. Free classes for doctors, nurses, and teachers under stress. A cheeky campaign about doing a 20-minute Pelorun when you are in a bad mood. Suddenly Peloton isn’t just “the bike company.” It is the feel-better company. And that broadens your audience from “fitness enthusiasts” to literally anyone with a brain.

Also, it solves the breadth problem. Because when you say “mental health through movement,” it covers yoga, cardio, meditation, boxing — every corner of the app. Instead of “we also have strength classes,” it is “we are the place to feel better, however you want to move.”

Campaign idea 2: Pelostrong

This one is cheekier. Peloton is a cycling term. But Peloton is not just cycling anymore. So what if, for a week, they rebranded as Pelostrong? It sounds silly. But silly stunts work. IHOP once changed its name to IHOB, International House of Burgers. It was ridiculous, and people mocked it, but traffic spiked and burgers sold.

Picture Peloton flipping its logo. The letters S, R, and G in a different color. Everyone arguing online about whether it is real. PR outlets writing think pieces. Meanwhile, the message is clear: Peloton is not just bikes. It is strength. And weightlifting is the second-most popular fitness activity after running. That is a massive addressable market.

They could double down by telling Pelostrong stories. Go to Reddit and you will find an entire underground archive of Peloton transformations. People who couldn’t finish a beginner spin class, now running marathons. People who picked up a dumbbell for the first time, now doing PR deadlifts. Package those into campaigns. Make them bingeable, like Netflix docuseries but for everyday athletes.

If Pelostrong feels too corny, there is a cleaner option. Split the app into “Strong by Peloton,” the way Marriott split its loyalty program into Bonvoy. It signals expansion without throwing out the parent brand. Either way, the goal is the same: shake people out of the “Peloton = bike” trap.

Expanding distribution: meet gym-goers where they already are

And then comes the fourth piece: gyms.

Peloton partnering with gyms sounds weird at first. Why would a gym let an outsider app in? But think about it. Gyms hate building their own digital platforms. They are bad at it. They want to manage equipment, real estate, and memberships. Peloton wants to make content. A revenue-sharing model could work beautifully.

Yes, gyms might worry about data sharing. Yes, they might not want to hand over their digital front door. But what if it is a hybrid app? Half their content, half Peloton’s. Everyone wins. The gym gets stickier customers who have a better experience. Peloton gets access to people who are already paying for fitness, instead of chasing non-exercisers who are the hardest sell on Earth. And even if someone cancels the gym and sticks with Peloton at home, the gym could keep a cut of that digital subscription forever. Imagine losing a member but still making money from them every month. That is a compelling pitch.

Put it all together and you have a roadmap.

Peloton can stop being the bougie spin app of the pandemic and start being the platform for working out and feeling good. The Netflix of fitness, but with a story that actually makes sense. A brand flywheel that spins instead of sputters.

And the funniest part? The answers have been hiding in plain sight. In Reddit threads. In half-baked ad ideas. In the very way people actually use the product.

How would you approach turning Peloton around?